Traveling to History: Thirty-Two

The Surf City Disaster

Eight Lives Lost When Excursion Steamer Capsizes

By James F. Lee

The Steamer Surf City

A Family in Mourning Celebrates the Fourth

Jennie Conant thought it might be fun for her family to end their day by taking the passenger ferry across the harbor to Beverly. She and five of her children, Ettie Mae, 19, Lillie, 16, Bertha, 7, Herbert, 5, and Doris, eight months, were celebrating the Fourth of July at Salem Willows.

Her husband, Herbert, had taken their eldest son, Bernard, 12, to spend the day in Rockport.

That the Conants were even there that day was remarkable. Just four days earlier, Ettie Mae, Jennie’s married eldest daughter, lost her two-month-old daughter in a tragic accident. Perhaps Jennie thought her daughter could use the distraction of a day out, but it must have been difficult for Ettie Mae, particularly because her little sister, Doris, was just six months older than her deceased baby.

As the afternoon wore on, Jennie faced another worry: the weather looked increasingly threatening. Should they still take the ferry across the harbor and then the B & D street car straight home to Danvers, or the more roundabout street car line through Salem? It was getting late, and the last ferry left the Willows at 5:50 p.m. She made her decision.

A Pleasant Fourth of July

The Surf City’s intended route

The Fourth that year, 1898, was very hot and breezy, typical for July on the Massachusetts coast. The Willows was an amusement park on Salem Neck, overlooking Salem and Beverly Harbors, a great place for families to pass a hot summer day enjoying the beaches, or picnicking under the delightful trees. It was easy to reach by street car.

In those days, restaurants lined the shore. Kids could ride the carousel, or the water chute, or devour Hobbs’ popcorn at the Willows Pavilion. And on this particular Fourth with news coming in of American victories in the war against Spain, brass bands were probably playing lots of patriotic music.

Across the harbor in Beverly, people flocked to Patch’s Beach and Mingo Beach, or further up the coast to West Beach, where families picnicked all day, and in the evening the boat houses would be illuminated with lanterns. Those wanting to spend the day further out in Salem Sound could take the ferry to Baker’s Island, enjoying the beach, walking on the rocks, or having lunch at the Hotel Wineegan.

The Surf City Arrives*

Sometime after 5:30 p.m., the steamer Surf City approached the pier at Salem Willows on the run from Baker’s Island with about 200 day trippers aboard, mostly women and children. Piloting the vessel was Henry C. Dalby, an experienced captain with first-class licenses as a master and a pilot. No doubt Dalby was keeping an eye on the weather.

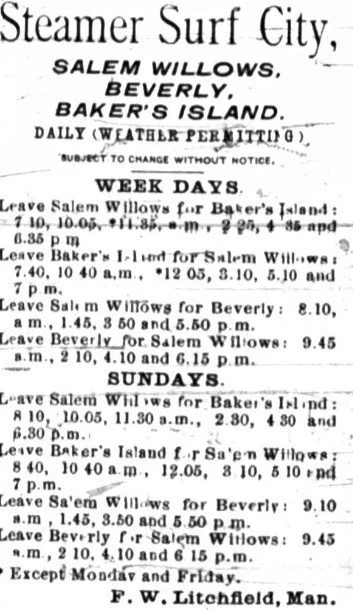

The Surf City’s schedule from the Danvers Mirror

The Surf City, owned by the People’s Steamboat Line of Boston, was 72 feet long,16 feet wide, and drew six feet of water. The vessel was licensed to carry up to 300 passengers. It had two enclosed passenger cabins on the main deck separated by a passage or companionway with a stairway leading to an exposed hurricane deck above. Forward of this upper deck was the smokestack and pilot house. The vessel traveled a continuous route throughout the day from Beverly, to Salem Willows, to Baker’s Island and back.

About three quarters of the passengers disembarked at the Willows, with the remainder staying aboard for the ten-minute crossing to Beverly. About 60 passengers purchased tickets at the Willows pier, joining those that had remained aboard the Surf City.

Because of the threatening weather, many of the passengers, including the Conants, crowded into the two main deck cabins.

A Sudden Squall

At about 5:50 p.m., the boat cast off from the Willows pier, following the zig zag course across the harbor, a route well-marked and familiar to Dalby. The Surf City headed northwest towards the Beverly shore and the Monument Bar Beacon before turning hard left back towards the Willows and Rams Horn Rock Beacon, just off Dead Horse Beach. Normally at this point, Dalby would turn the steamer hard right, intending to follow the channel towards Lobster Rocks and the pier at Beverly.

As the Surf City approached Rams Horn, the weather turned. Tremendous flashes of lightning illuminated a blackening sky. Many of those who had been on deck made their way to the shelter of the crowded main deck cabins – as it turned out, a tragic mistake. A sudden strong wind from the southwest struck the steamer head-on. Dalby called for full steam, but the force of the wind was so great the boat backed, then swung around, taking the full force of the wind across the port side, blowing the Surf City off course back towards Monument Bar.

The wind tore the upper-deck awning, which acted like a sail, careening the boat onto its starboard side in about seven feet of water. The boat struck the edge of the bar.

A three-foot wall of water crashed over the hurricane deck, sending a torrent down the stairs and through the cabin door like a waterfall. Passengers in the cabin, thrown about like ragdolls, crowded to the door in panic but were forced back by the inflowing sea. The Beverly Evening Times reported that water rushed into the starboard side windows “cascading through the windows like cataracts.” People frantically kicked out the port-side windows, handing fellow passengers out to those on deck. Mothers screamed as they fought to save their children.

“The wind seemed to strike squarely on the side of the boat, and the passengers were blown to the other side. In an instant, there was a confused heap of arms and legs and bodies, then the boat went over.”

- Bertram Ham, Beverly

Some passengers had been seated on deck chairs on the main deck when the storm hit. Those on the port side were thrown violently against the cabin bulkhead, while many of those on the starboard side were pitched into the sea. The bow submerged almost immediately, throwing passengers seated there overboard.

At the wheel, Capt. Dalby pulled at the distress whistle, and fearing the pilot house might submerge, he punched out the windows as a possible means of escape. When the boat settled with the pilot house above water, he kicked open the cabin door and ran on deck to aid the passengers. The storm lasted minutes and was over as suddenly as it started.

Dalby later claimed that the boat was hit by two storms simultaneously, one from the east, the other from the west, “with a terrific force, and that a whirlwind followed.” He said there was no time to use the vessel’s lifeboats.

Chaos on Board

In an instant, those aboard were fighting for their lives.

The point of disaster

In water nearly up to her waist, Jennie Conant broke her way out of the cabin through a window and pulled four of her children to safety. Ettie Mae was still in the cabin unconscious. Her mother desperately pulled at her body, ripping her daughter’s clothes in her frantic attempts, but she could not move her.

She dragged unconscious Lillie and Herbert along the deck, making her way by holding on to the precariously tilting boat’s railing.

Also in the cabin when the storm hit was Charles Chase of Beverly, returning home from the Willows with his family. Chase said the boat seemed to lift and settle, and the next thing he knew water came rushing into the cabin. He quickly lifted his family and others through the windows, saving fifteen people.

Video: Salem Willows overlooking Beverly Harbor

Those on deck also fought for their lives. Gertie Fowler, 17, of Marblehead, who boarded at the Willows but couldn’t find room in either of the cabins, was thrown overboard when the Surf City foundered. She sank at once, but fought her way back to the surface, where she grabbed a stanchion on the hurricane deck, holding on until her strength gave out. She went under again, and resigned herself to die, feeling, she said later, calm and without fear. But she surfaced again and this time was grabbed by Ida Bushby, 25, a music teacher from Peabody, who held on to Gertie’s wrist and wouldn’t let go until another passenger was able to help get her on to the deck.

Bertram W. Ham of Beverly was standing on deck near the pilot house when the force of the wind lifted him off his feet and into the water. Ham, a non-swimmer, told the Beverly Evening Times, “The wind seemed to strike squarely on the side of the boat, and the passengers were blown to the other side. In an instant there was a confused heap of arms and legs and bodies, then the boat went over.”

Help Arrives Quickly

Several passengers said that it seemed like an eternity until rescue boats arrived, but in fact the plight of the Surf City was in full view of those on shore and in vessels anchored in the harbor. Rescuers arrived within minutes.

The Boston Herald’s drawing of the capsized Surf City

Members of Beverly’s Jubilee Yacht Club at Tuck’s Point sprang into action sending boats out to the rescue, pulling out dozens from the water. The whale boat from the schooner Yale was one of the first rescue boats to reach the stricken Surf City. Crewmember Isaac Anderson tied a rope around his waist and dove into the flooding cabins searching for survivors. Another boat saved two quick-thinking boys, who climbed the guy wires holding the steamer’s smokestack.

One of the last passengers taken from the steamer was Margaret Nolan of Beverly, who adamantly refused rescue until all others were safe.

As bodies of victims were recovered, they were brought back to the dock at the Yacht Club in Beverly, which became a makeshift infirmary – and morgue.

On Baker’s Island, the fifty or so passengers stranded there grew impatient and increasingly concerned when the Surf City did not return to pick them up. Of course, they had no idea of the tragedy that had occurred. A small tug set out from Beverly that evening to pass the news, arriving at 10:30 p.m. on the island. The tug was able to carry a few passengers back, but the remainder spent the night at the island’s sole hotel, which graciously made space for them.

Also helping was Capt. Moses Priest, whose yacht Wilhelmina weathered the storm that day anchored near Misery Island. Priest rowed to Baker’s Island in a small boat, leaving at 9 p.m., to pass on the news. While there, he was able to get a list of those still on the island. Priest then rowed back to Beverly with the list and with four of the stranded, an astonishing feat, especially at night. The next morning, the Wilhelmina and another vessel rescued the remaining victims.

The North Shore Mourns

Eight people died in the Surf City disaster, two adults and six children, five from Beverly and three from Danvers. The oldest was 28 and the youngest was four. As news of the tragedy spread, people flocked to Beverly that night searching for loved ones, not knowing if they were on the boat or still on Baker’s Island. Rumors abounded regarding how many had perished. Most of the injured were initially treated at the yacht club and then either released or taken to Beverly Hospital. Some were treated at people’s homes.

Video: Walnut Grove Cemetery, Danvers

This was the case with Mrs. Conant, who was taken with her children Doris and Bertha to Mrs. Andrews’ house on Water Street, where doctors revived them. Later that night, they sought shelter at Mrs. Conant’s cousin’s house on Cabot Street.

The dead, including Lillie and Herbert Conant, Jr., were taken to Lee and Cressy undertakers on Cabot Street, across from today’s First Parish Unitarian Universalist Church, to be identified by grief-stricken family members, some survivors of the disaster themselves.

In fact, the last victim to be identified the night of the disaster was Lillie Irene Conant, known as Renie to her friends and family. According to the Beverly Evening Times, her cousin, Nellie, who the newspaper said was aboard the Surf City and rescued earlier that day, came into the Lee and Cressy funeral parlor at around midnight, asking if any unidentified bodies remained. Mr. Lee took her to the back where one body still lay, and with a scream Nellie identified her cousin. A Beverly police officer then took Nellie home to Danvers to break the news to her family, not knowing of course, that her aunt was still in Beverly.**

And sadly, the last victim to pass away was Ettie Mae Emerson, Mrs. Conant’s eldest daughter. Ettie Mae was pulled from the boat unconscious and taken to Beverly Hospital, where she was listed in critical condition. She died the next morning at 6:00.

The next day at the site of the wreck, divers searched the boat for more victims under the gaze of hundreds of people lining the shore. Thankfully, there were no more.

One of the saddest aspects of the disaster was the debris left in the water, the personal effects of people who had lost their lives so suddenly. For days, people found clothing, hats, baskets, even a gold watch, A diver hired by the boat’s owner to search for any remaining bodies, came up from a dive with a parasol marked with the name Webber – one of the victims.

Victims Buried

Several funerals were held during the course of the week in Beverly and Danvers. In Beverly, the first was held on Wednesday afternoon for Theresa Kennedy, 4, repeatedly misidentified in newspapers as John Kennedy in the aftermath of the disaster. Her service was held at the home of her grandparents on Cabot Street.

On Thursday, the Second Congregational Church was bedecked in floral tributes at the service for Grace Snell, 13, where a quartet sang “Sleep On, Sweet Child,” and other hymns. A group of her classmates attended, all crying as they passed by her coffin.

A double funeral service was held for Nellie Cressy, 21, and Myra Fegan, 16, members of the Judson Street Universalist Church, where the American Legion is today. A large crowd watched as their white caskets were placed in a hearse and led in a procession up Cabot Street and then along Charnock Street to the cemetery at the end of the street. Myra had graduated from Beverly High School just the month before.

Katharine Webber’s funeral was held at her home on Highland Avenue, the room where she lay filled with flowers. Friends and family of the young stenographer attended as did members of the Washington Street Sunday School, where she was a member.

Ram’s Horn beacon from the Salem Willows today

And in Danvers, funeral services were held at the packed Maple Street Church also on that Thursday. Flowers surrounded three white coffins, each with the names and dates of the three Conant children who perished in the Surf City disaster. Three hearses traveling abreast led the way to Walnut Grove Cemetery where the siblings were buried together.

The pain Mrs. Jennie Conant suffered that day must have been unbearable: in less than a week, she had lost three children and a grandchild.

Post Script

The Surf City was raised, towed to Boston, and then sold at auction in September 1898 to satisfy the claims of the crew for back wages and of creditors for coal and other supplies. The steamer, greatly altered and renamed the Pauline, was initially used to transport prisoners to Boston’s Deer Island House of Industry.

An inquest was held in Salem on August 2 at which five survivors of the disaster, including Charles Chase, spoke favorably on Captain Dalby’s behalf. The judge said he would file a finding later. I can find no record of a finding.

Notes:

*According to the late Tom Duggen, past Commadore of The Jubilee Yacht Club in Beverly, the Surf City drew about six feet of water. Given that normal tides in the harbor run from about 11 feet at high tide down to minus 2 at low, the boat would need to be in 12 feet of water at low tide to make the crossing safely. This meant the Surf City had to take a zigzag route, following the channels as they were marked in 1898 and avoiding sand bars. Phone interview 5/10/2024

**The Boston Traveler identified Nellie as the daughter of Mrs. Conant, which clearly she was not. It is possible that Mrs. Conant took her niece on the outing, or perhaps Nellie was the daughter of Mrs. Conant’s sister-in-law.

Sources:

Much of this account was pieced together through newspaper sources. Newspapers include:

Beverly Citizen and Beverly Evening Times, accessed online through Beverly Public Library

Salem Evening News, information provided by the Salem Public Library Reference Department

Danvers Mirror, accessed online through the Peabody Institute, Library of Danvers

Boston Daily Globe, accessed online through newspapers.com 6/20/2025

Marblehead Messenger, accessed online through Abbott Public Library, Marblehead

Boston Traveler, accessed online through Boston Public Library, Digital Commonwealth, 7/3/2025

Boston Evening Transcript, accessed through newspapers.com 7/8/2025

Massachusetts, Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988, accessed through Ancestry.com., 6/27/2025

Massachusetts, U.S. Death Records, 1841-1915, accessed through Ancestry.com., 6/27/2025

Photo Credits:

Surf City photo, Surf City, 1891, "Ships Portraits" Bradlee Collection, [neg. 15018].Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum; Intended route, Salem, Marblehead and Beverly Harbors (detail), NOAA Chart #13276, Northshore Harbormasters Association, www.harbormasters.org; Surf City Ad, Danvers Mirror, July 2, 1898, p. 2, accessed online through the Peabody Institute, Library of Danvers; Point of disaster, Northshore Harbormasters Association, www.harbormasters.org; Surf City drawing, The Boston Herald (detail), July 4, 1898, information provided by the Salem Public Library Reference Department; Ram’s Horn Beacon (Photo by Carol A. Keller)

Video Credit: Carol A. Keller