Traveling to History: Thirty-Three

Cornwall Iron Furnace:

A Vestige from a Long-ago Industry Remains Intact

By James F. Lee

The big wooden doors creaked open and we entered the charging room, a barnlike space with a wide-planked floor, vaulted ceiling, and stone walls. Shafts of sunlight penetrated the gloom through arched windows. Three wagons were lined up along the wall to the right.

The Cornwall Iron Furnace in Cornwall, Pennsylvania (Courtesy of Cornwall Iron Furnace)

At the far end, a small hole in the floor looked down into a chimney lined with clay and brick.

The Cornwall Iron Furnace in Cornwall, Pennsylvania, is the only remaining intact charcoal blast furnace in the western hemisphere. When the 32-foot, limestone furnace closed in 1883, it was like the owners locked the door and walked away. The furnace itself is housed within the confines of a Gothic Revival sandstone building built in the mid-19th-Century.

“It’s all original, said Brian Bachman, our guide. “You could start this thing up now and run it.”

In the charging room, wagon loads of local iron ore, limestone, and charcoal from nearby woods were dumped into the furnace, like feeding the mouth of the beast.

On a table were products used in the smelting process, including charcoal, iron ore from the strip mine, limestone, and slag waste. Brian handed us a sample of each.

“The limestone acts like a flux when the iron ore and slag melt, separating the slag from the iron ore,” he said.

The charging room at the Cornwall Iron Furnace, where charcoal, limestone, and iron ore was unloaded before being deposited in the chimney at the rear.

Next, watching our step in the dim lighting, we descended a wooden staircase to see the Great Wheel. Looking up, we could see the enormous timbers supporting the ceiling and the charging room above us.

The wheel once powered the bellows that blasted air into the furnace. It is impressive, weighing four tons and measuring 24 feet in diameter. Brian flipped a switch starting the wheel rotating.

Technology rendered the wheel obsolete, and it was later replaced by steam engines that could power the bellows more efficiently. One of those steam engines is still there, located in a side room nearby.

Eventually, we made our way down to the casting room, the bottom of the furnace, where the molten iron gathered to be formed into stove plates, frying pans, kettles, cannon balls, or even cannons. To cast stove plates, for example, two workers would transport molten liquid with a ladle and pour it into molds.

“It’s all original. You could start this thing up now and run it.”

Pig iron was formed when workers pulled a plug from the bottom of the furnace, allowing the liquid to run along small channels into 100-pound forms that would be sent to the forge house for further processing. Some pig iron was shipped by barge or train throughout Pennsylvania and to neighboring states.

The entire process took about twelve hours from charging room to casting room, allowing for two shifts to work around the clock.

It was hot, dangerous, backbreaking work.

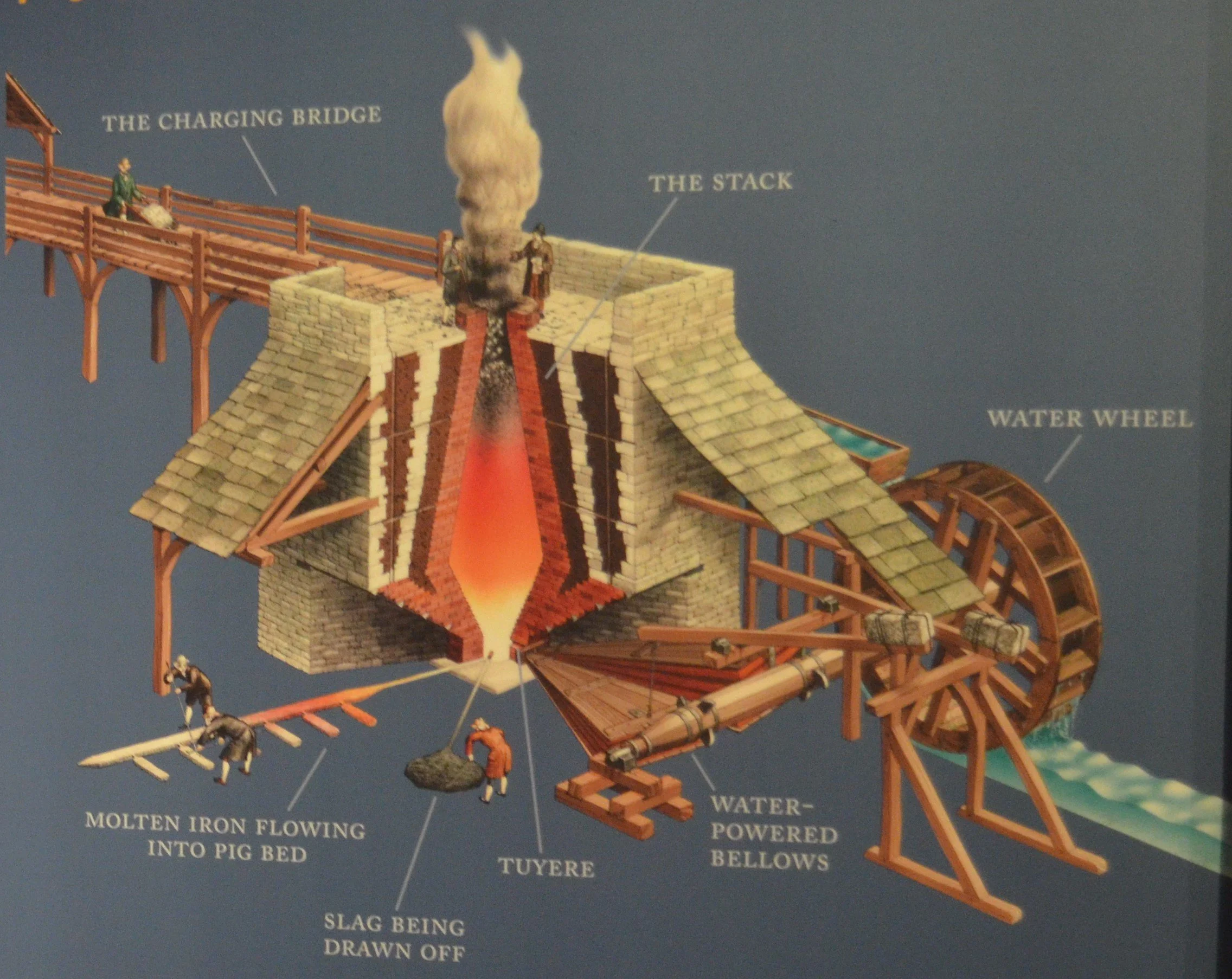

A diagram of the Furnace in operation

The Cornwall furnace was really a plantation where all aspects of the blasting process took place, from chopping down and burning trees in the nearby forests to create charcoal, to mining the ore and limestone from the nearby hills, to the skilled labor required in the manufacturing process.

Workers there bought their supplies from the company store. I wondered if the workers were paid in scrip as was typical in the coal industry at the time. But that was not the case.

“The workers at Cornwall were paid in cash,” said Michael Emery, Acting Site Administrator of the Cornwall Iron Furnace.

Housing was provided to many laborers at the miners’ village on Boyd Street. On our way in to the Iron Furnace, we passed by this row of lovely stone houses, notable by decorative quoins at the corners, diamond shaped attic windows, and flat arches and sills, architectural details unusual for workers’ homes. These houses are now private homes.

Today, many of the buildings that were part of the plantation are still there, although not open to the public. They include a blacksmith shop, wagon shop, smokehouse, and a charming Victorian paymaster’s office. The open pit mine, where iron ore and dozens of minerals were extracted, is now filed with water, the result of Hurricane Agnes in 1972.

A closeup of the 24-foot water wheel. The wheel is original and the axle is restored.

The Cornwall Iron Furnace today houses an impressive museum that gives the history of the furnace and examples of products and the people who worked there, including furnace workers, farm laborers, charcoal makers, domestic servants, and millers.

On display at the museum were workers’ boots, cannon balls, a handheld tallow lamp furnace workers used as a light source, and a cannon made for Continental forces in the American Revolution. Two cabinets contain a fascinating collection of minerals mined on site, including quartz, mica, malachite, magnetite, pyrite, chalcopyrite, and hematite.

In the museum, we learned that enslaved workers played a significant role in the ante-bellum workforce of the furnace. A panel in the museum explains that the first record of an enslaved person at Cornwall was in 1764. By 1779, fourteen of the 23 workers at the furnace were enslaved, toiling as both skilled and unskilled laborers. Pennsylvania passed an Abolition Act in 1780, leading to the gradual demise of slavery in the commonwealth. The last slave appearing in furnace records was in 1798.

The casting room at the bottom of the furnace, where molten iron ore was formed into molds.

The original furnace on this site started operating in 1742. Much of what we see today, though, dates from the mid-19th Century construction. The furnace stopped producing in 1883, when larger-scale, more efficient methods of iron smelting were coming on the scene.

Following World War II, the owners of the furnace sold the property to Bethlehem Steel, which continued mining from the open pit, but the family, descendants of former owner Robert Coleman, held on to the furnace itself, where it sat idle. In 1932, the largely untouched furnace was donated to the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to preserve as a museum.

Visitors to the museum are encouraged to touch these iron products.

A display case in the museum showing minerals mined at the furnace site.

Welcome to Cornwall Iron Furnace.

Photos by James F. Lee unless otherwise noted