Traveling to History: Twenty Three

Phillis Wheatley’s Boston: Vestiges of the poet’s life remain today

By James F. Lee

A small blue plaque in Boston’s Chinatown near the corner of Tyler and Beach Streets commemorates a long-ago event. At this spot, in 1761, the ship Phillis landed a cargo of 75 human beings at Griffin’s Wharf. One of the survivors was a seven-year-old child all alone, kidnapped from her home in West Africa. Twenty-one of her fellow Africans perished during that crossing.

This statue of Phillis Wheatley is part of the Boston Women’s Memorial on the Commonwealth Avenue mall. (Courtesy of Michael Bergmann)

It’s hard today to imagine this busy urban intersection as waterfront, just as it is hard to imagine that frightened girl alone in an alien world.

She was noticed, though, by John Wheatley, a businessman; he purchased her, named her Phillis, and brought her into his home at the corner of King and Mackerel Streets (today’s State and Kilby Streets) about a half mile from the wharf.

John Wheatley and his wife Susannah soon noticed the girl’s precocious ability to learn. She quickly mastered English and found expression in poetry, an 18th-century style imbued with classical and Christian influences, often written in couplet form. She commemorated events and wrote elegies of people famous and obscure.

The Old State House is dwarfed by modern buildings. The Wheatley’s house was located to the left of the closest pedestrian crossing sign. (By Jax4260 – Own Work, Creative Commons — Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International — CC BY-SA 4.0)

Twelve years after she was purchased, and still enslaved, Phillis Wheatley became the first African American to publish a book, when “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral” was released in London in 1773. Her admirers included George Washington, Voltaire, and English literary critic Elizabeth Montagu.

Wheatley lived most of her life in Boston, a small, intimate world for White and Black, and while most traces of her life are gone, a few remain today.

Wheatley’s Boston

Looking down State Street through a window in the Old State House. (Photo courtesy of Katie Turner Getty)

King Street, when Phillis Wheatley lived there, was the commercial heart of Boston. Shops sold goods from all around New England and the British empire, including wigs, silks, coffee, and cheeses, many of those items off loaded at Long Wharf at the foot of King. Merchants met and discussed trade at the Royal Exchange Tavern. Patriots, such as Paul Revere, frequented the Bunch of Grapes tavern across Mackerel Street from the Wheatley home. It is entirely possible that Phillis Wheatley could look out the window and see slaves sold outside these taverns.

Dominating at the head of King Street was the Old State House, the seat of British political power, scarcely 100 yards from the Wheatley house. This three-story brick Georgian building with massive cupola is a striking presence now, even dwarfed by the surrounding modern buildings, but in the 1770s, it must have presented an awesome sight. Seven-foot sculptures of the lion and unicorn, the symbols of British power, still flank the giant clock on the east façade, replacements for the originals. The Council Chamber of the Royal Governor and the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court met here.

The building is one of the most visited places in Boston and site of the Boston Massacre.

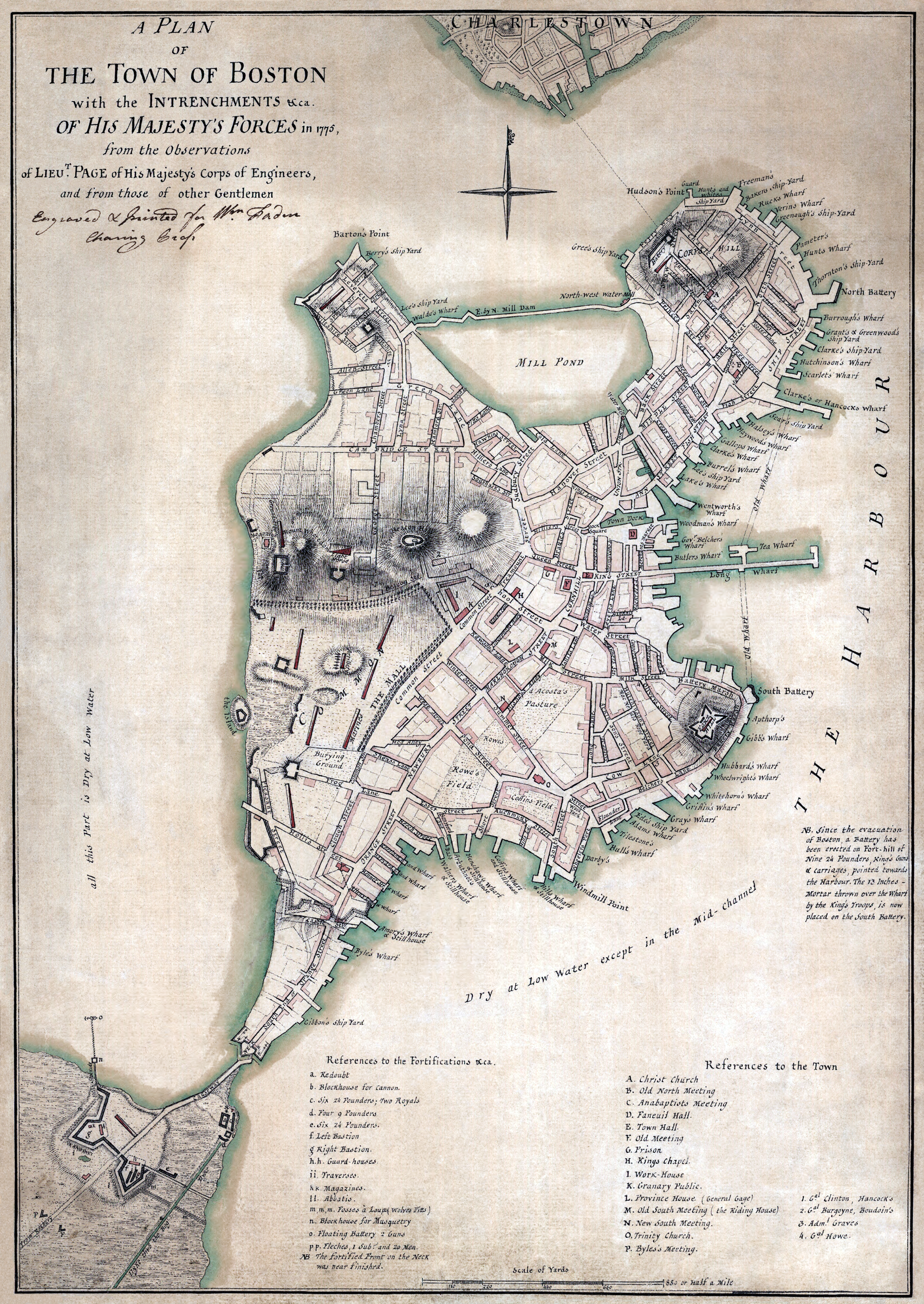

A Plan of the Town of Boston, 1775. Griffin’s Wharf can be seen to the east below Fort Hill. (By Sir Thomas Hyde Page. Library of Congress, G3764.B6S3 1777 .P3 Faden 32. Modifications by Durova). {{PD-US}}

We don’t know if Wheatley witnessed the Boston Massacre, but it is hard to imagine that she would have missed it. Reports that night said disturbances had broken out before the shooting to the north and east of the Old State House, which would have put the Wheatley household in the center of things. The British soldiers fired on the crowd from in front of the Old Custom House on King Street, diagonally across the street from the Wheatley home.

At any rate, Wheatley felt moved enough by the shooting to write a poem, “On the Affray in King-Street, On the Evening of the 5th of March,” commemorating the sacrifice of the fallen patriots.

Phillis Wheatley’s support of the patriot side was tempered by the skepticism and anger of an enslaved person denied freedom by a cause that called for liberty. Other patriotic poems include, “On the Death of Mr. Snider, Murder’d by Richardson,” describing the shooting of a young man by a British government official a month before the Boston Massacre. In this poem, she describes the victim as “the first martyr for the cause…” In 1775, she wrote a poem praising George Washington, and sent him a copy.

Detail of 1775 map of Boston, showing Dock Square and vicinity. The Wheatley’s house was at the northeast corner of King and Mackerel Streets. (By Sir Thomas Hyde Page. Library of Congress, G3764.B6S3 1777 .P3 Faden 32. Modifications by Durova, Derivative work: M2545). {{PD-US}}

Washington responded to the poem in February of 1776 from his military headquarters in Cambridge in which he complimented the “elegant lines.” Knowing full well that she was a former enslaved woman, he invited her to visit him in Cambridge, writing, “I shall be happy to see a person so favoured (sic) by the Muses, and to whom Nature has been so liberal and beneficent in her dispensations.” There is no record of her visiting Washington there or anywhere. The house still stands, known as Longfellow House, a beautiful yellow Georgian mansion on Brattle Street in Cambridge.

Religion was central to Phillis Wheatley’s life. She was a Congregationalist like John and Susanna Wheatley. But unlike the Wheatleys, who worshipped at New South Church that stood at the corner of Summer and Bedford Streets, Phillis Wheatley was a congregant at the Old South Meeting House still standing on the corner of Washington and Milk Streets, its tower clock a familiar landmark then as now.

Old South Meeting House on Milk Street. This was Phillis Wheatley’s house of worship. (NPS photo)

The Old South Meeting House was one of the largest buildings in Boston and site of community meetings as well as worship. Many of the worshippers there in Wheatley’s time were people of color. Today, a statue at the church honors her, and on display is a first edition of “Poems on Various Subjects.”

Interior of the Old South Meeting House. (By Daderot – Own work, CCO 1.0, Public Domain)

Phillis Wheatley left Boston briefly in 1773 sailing to England to promote her book. While in England she self-emancipated, taking advantage of English law, and returned to Boston a free woman.

In 1778, she married John Peters, a free Black man, at the New Brick Congregational Church on Hanover Street near the site of today’s Galleria Umberto.

Not much is known about Phillis Wheatley after her marriage. She published a few poems and tried unsuccessfully to publish a second book. She died at age 31 on December 5, 1784. Her funeral was held at the home of Dr. Thomas Bulfinch on Bowdoin Square. The house no longer stands, but a marker denotes its location near the Bowdoin MBTA stop. Because of the proximity of the Bulfinch house to Granary Burial Ground, there is some speculation that she may be buried there. Phillis Wheatley’s grave is unmarked; a fate borne by most African Americans at that time.

An advertisement in a Boston newspaper, May 10, 1773, for an enslaved person to be sold. At about this same date, Phillis Wheatley left Boston for her journey to London and self-emancipation. From Slavery Adverts 250 Project. Boston Evening-Post, May 10, 1773 (America’s Historical Newspapers, Readex/NewsBank)

Phillis Wheatley Remembered

Phillis Wheatley’s writing desk. Following her death, this desk was sold at auction to help pay her debts. (Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society https://www.masshist.org/database/363)

Few artifacts related to Phillis Wheatley exist. The Massachusetts Historical Society on Boylston Street has a mahogany, Chippendale writing desk assumed to be Wheatley’s. It was sold at auction by her husband after her death.

The Historical Society also has a poem written in Wheatley’s hand, “A Poem on the Death of Charles Eliot, aged 12 Months.” Her handwriting is superb, clearly that of an educated person.

Griffin’s Wharf no longer exists, but historic Long Wharf does, jutting out from State Street. At the end of the wharf overlooking Boston Harbor a placard tells the story of the Middle Passage and Boston’s role in it. On the other side, the placard tells the story of individuals caught up in the Middle Passage, including Phillis Wheatley.

On Commonwealth Avenue the Boston Women’s Memorial honors Phillis Wheatley, Abigail Adams, and Lucy Stone. Wheatley leans on her pedestal in a seated position wistfully looking into the distance. The seven-year-old girl kidnapped from Africa is now a revered literary figure.

Image of Phillis Wheatley from the frontispiece of Poems on Various Subjects. Library of Congress. {{PD US}}

Postscript:

“The Golden Triangle of Trade”

On the wall of the Forest Street post office in nearby Medford, a three-panel mural was once on display depicting the city of Medford’s economic history of ship building, brick making, and rum distilling. The center panel displayed an enslaved African carrying sugar cane on his back, and in the background was a map of the Atlantic world emblazoned by a triangle symbolizing the triangular trade of rum, molasses, and slaves.

The mural was controversial, and it has since been covered over, but it clearly showed the role the slave trade played in Medford’s history. Timothy Fitch, who lived in Medford, was the owner of the Phillis that brought Phillis Wheatley to the New World.

Portrait of Timothy Fitch about 1760 by Joseph Blackburn. Fitch, a Medford merchant, owned the ship Phillis. (Collection of the Peabody Essex Museum)

Source:

Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage, by Vincent Carretta

The Odyssey of Phillis Wheatley, by David Waldstreicher

Medford Historical Society