Traveling to History: Twenty

OXYGEN, SEDITION and MOZART

By James F. Lee

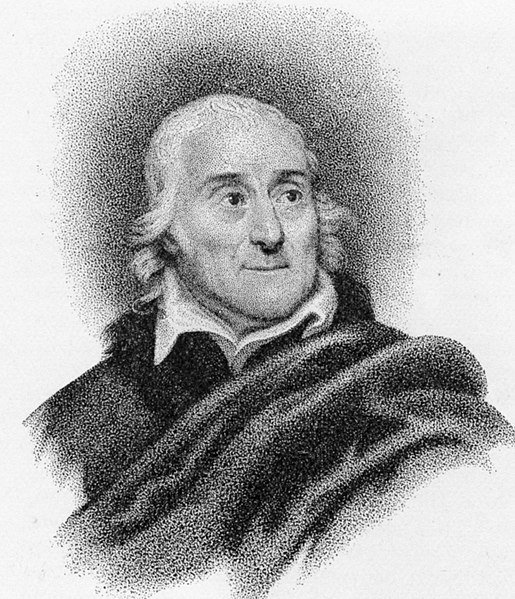

Portrait of Joseph Priestley, 1794 by Ellen Sharples. National Portrait Gallery (UK). {{PD US}}

For a short time –between 1794 and 1818 - two small towns on the Susquehanna River were the center of the world. Well, in a way.

Northumberland and Sunbury, Pennsylvania, counted among their inhabitants three men of lasting fame: Joseph Priestley, the discoverer of oxygen; Thomas Cooper, a firebrand newspaper editor and victim of President Adams’ Sedition Act; and Lorenzo Da Ponte, Mozart’s librettist.

Nothing remains of the latter two’s residency, but in Northumberland Borough, Joseph Priestley’s grand Georgian mansion still overlooks the Susquehanna River.

Priestley, an Englishman, was celebrated in Europe as a scientist. In 1775, Priestley made his greatest scientific discovery, oxygen gas, and published his findings.

The Joseph Priestley House in Northumberland, Pennsylvania. This is the side of the house facing the Susquehanna River. (Photo by James F. Lee)

A Dissenting (against the Church of England) clergyman, he rejected the Trinity and the divinity of Christ, heretical thinking that was often met with violence.

On July 14, 1791, during an outbreak of anti-Dissenter hysteria, a mob attacked his house in Birmingham, England, destroying it, his library, and laboratory. This violence led him to seek sanctuary in the United States.

Priestley’s arrival in the New World, generated lots of interest. He was greeted warmly by President Washington and other luminaries, offered a professorship of chemistry at the University of Pennsylvania, but chose to settle in Northumberland. Here he built his grand house designed in large part by his wife Mary. While living in Northumberland, Priestley continued his scientific experimentation and expounded on his Unitarian beliefs.

Initially, Priestley hoped to found a liberal community in the Pennsylvania frontier where he would be free from religious persecution. The year before he arrived, two of his sons along with friend Thomas Cooper scouted out the area.

A microscope owned by Joseph Priestley (circa 1780-1790) made by William and Samuel Jones of London, on display at the Priestley House. (Photo by James F. Lee)

The community never materialized, but Priestley house remains, where he spent the last ten years of his life, passing away in 1804.

The two-and -a-half story Georgian-style, wooden clapboard house built in 1797 sits on a slight rise with a view of the Susquehanna River in a neighborhood of small homes in the Borough of Northumberland. It is a National Historic Landmark. A distinctive feature is the roof-top belvedere surrounded by a railing, offering splendid views of the river and surrounding landscape. Priestley had a laboratory constructed in a wing of the house, arguably the first well equipped scientific laboratory in the country. Within this laboratory, he identified carbon monoxide.

French-made clock given to Joseph Priestley by the Marquis de Lafayette. (Photo by James F. Lee)

Inside, the rooms are decorated to represent the time of Priestley’s occupancy and contain many artifacts belonging to the scientist, including, most impressively, his microscope, a beautiful wooden and metal instrument on display in the downstairs parlor.

Some artifacts are exquisite, such as the French mantel clock on an elaborate ivory and gold leaf pedestal topped with gold-plated doves. This was a gift to Priestley from the Marquis de Lafayette.

Other Priestley-related items include a chess set, tea service, telescope, spectacles, glass prism, and dining room table, chairs, and china.

Portrait of Thomas Cooper on display at the University of South Carolina, where he served as president when it was South Carolina College. (Photo by John L. Moore)

A frequent visitor to the house was Thomas Cooper, the editor of the Northumberland Gazette. Cooper, a radical lawyer, scientist, and philosopher, was friends with Priestley in England and both emigrated to the United States at about the same time. His political and philosophical writings were widely read in Britain and the United States. Cooper was friends with Thomas Jefferson and James Madison and supported Democratic-Republican principles. Even Federalist John Adams grudgingly admired him. He lived in Northumberland between 1795 and 1811.

Cooper was outspoken in his criticism of President Adams, eventually getting charged with sedition under the notorious Alien and Sedition Acts. Cooper was convicted, fined $400, and served a six-month prison sentence in Philadelphia.

Cooper’s actions “helped establish the right to criticize a sitting president,” said John Moore, a writer of popular history and historical interpreter who has studied Cooper.

After his release from prison, Cooper lived briefly in the Priestley home. He lived in Northumberland until 1811.

Could this house on the corner of Water and B Streets in Northumberland be the house where Thomas Cooper lived in Northumberland? (Photo by James F. Lee)

Nothing remains from Cooper’s residence in Northumberland. According to Moore, local tradition identifies the house at the corner of Water and B Streets in Northumberland as a possible residence of Cooper.

Cooper accepted a professorship at Dickinson College and then the University of Pennsylvania, later becoming president of South Carolina College (now University of South Carolina).

In 1811, Italian immigrant Lorenzo Da Ponte arrived in Sunbury, directly across the Susquehanna River from Northumberland. Although Jewish by birth, Da Ponte became a Catholic priest for a time, and later a poet, professor of languages, and writer. He led a wandering life throughout Europe, at one point becoming the court poet and librettist of the Austrian emperor in Vienna, where he wrote the libretti for Mozart’s operas The Marriage of Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Cosi fan tutte.

Lorenzo Da Ponte (circa 1822) from an engraving by Michele Pekenino. {{PD US}}

He continued his wanderings, ending up in London, where he struggled to make ends meet. Eventually, in 1805, debt and bankruptcy drove him to New York seeking new opportunities. He then settled in Sunbury where his wife’s family were successful merchants. In Sunbury, he entered many business enterprises selling brandy, peddling groceries, and teaching Italian, but proved a poor businessperson, and in 1818 returned to New York, where he found success as a professor of Italian and a promoter of opera.

He died in New York in 1838.

This Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission marker on Market Street in Sunbury, Pennsylvania. This marker is near the former location of Da Ponte’s residence. (Photo by James F. Lee)

Yet, for seven years the librettist for the world’s most renowned composer lived in this frontier town. Today, nothing is left from Da Ponte’s time in Sunbury, except for a plaque near the former location of his residence.

Why did these men, well known and established in Europe, come to Pennsylvania?

“These were frontier towns,” said Moore. “Financial opportunities were wide open,” The Susquehanna River provided transportation for goods and news between central Pennsylvania and Philadelphia.

It was a chance to find fortune, or perhaps a new beginning.

A USGS map showing the location of Northumberland and Sunbury, Pennsylvania. The location of Priestley’s house is marked in Northumberland. (Source: USGWarchives.us)