Traveling to History: Twenty Six

A Well-Traveled Statue

Greenough’s Statue of Washington at the National Museum of American History Has Had Many Stops Along the Way

By James F. Lee

Greenough’s George Washington statue today in the National Museum of American History. (Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution)

Greenough’s Statue

Horatio Greenough by Rembrandt Peale, 1829. National Portrait Gallery. (CC0 1 CC0 1.0 Deed | CC0 1.0 Universal | Creative Commons)

On the second floor of the National Museum of American History, thousands of visitors have viewed the 12-ton, white marble statue of George Washington. The first president is seated on a chair, his right hand pointing skyward, a sheathed sword in his left. Behind him stand small statues of Columbus (the Old World) and a Native American (the New World).

Many seeing the statue for the first time ask the same question: why he is wearing a toga and sandals?

That is an interesting story, but even more compelling is how the statue got there in the first place; a story of ships, barges, oxen-drawn carts, cranes, and flatbed trucks.

The sculptor, Horatio Greenough, was a young American artist just making a name for himself when Congress pegged him in 1832 to create a statue of the country’s Founding Father. With commission in hand, and $5,000 to spend, he headed to Italy, selected white Carrara marble from the hills of Tuscany for his material, and set to work at his studio in Florence.

Eight years later, he was ready to send his creation home to the United States.

It was an arduous undertaking hauling the massive statue in a cart drawn by oxen from Florence to Leghorn, where John A. Delano, captain of the ship “Sea,” waited to carry Greenough’s statue home. The ship’s sides were strengthened, and hatches enlarged in preparation for the voyage.

On American Soil

Delano delivered his payload at Washington’s Navy Yard on the Eastern Branch (now Anacostia River) on a hot July day in 1841, also making a cool $5000 from the U.S. Government for the journey.

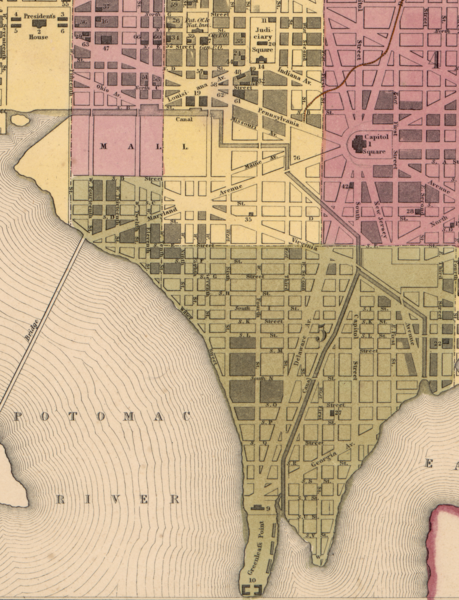

Map of Washington Showing Washington City Canal, 1851, by S. Augustus Mitchell. (Library of Congress Geography and Map Division, Washington, D.C).

Once out of the hold of the “Sea,” the statue’s destination was the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol but getting there proved a difficult problem, one that nobody seemed to want to tackle. Coming forward, though, was Captain William Easby, who offered to take on the responsibility and was quickly awarded a contract by a relieved Congress.

Easby was uniquely qualified for the task. He was a mathematical wizard and shipwright, employed for many years at the Navy Yard. He was a shipbuilder, and later owned his own shipyard, where he designed and built vessels and engaged in construction projects around Washington.

Easby approached the problem pragmatically. Taking advantage of the Washington City Canal, which emptied into today’s Anacostia River just west of the Navy Yard, the statue was loaded onto a scow and floated up the canal towards the capitol. The canal has been long filled in, but you can still see where it emptied into the river, a rectangular indentation near the D.C. Main Pumping Station.

A portrait of Captain William Easby. (NH 54952 – Courtesy of Naval History and Heritage Command)

The statue traveled north roughly along today’s Second Street, SW and then cut northwest passing near the capitol building, where it was offloaded near the intersection of Third Street, SW and Maryland Avenue, SW, not far from today’s Botanic Garden.

Now came the hard part. Once off the barge, the statue had to be dragged on rollers from Maryland Avenue up Capitol Hill around to the East Portico by a human-powered capstan and cables, a painstaking process that took several days, and one that drew lots of spectators. They cheered as the statue was raised 26 feet to the level of the Rotunda floor by a Gin pole erected at the east entrance.

It is likely that enslaved workers, possibly leased to the Navy Yard, provided the human labor moving the massive block of marble.

By December, Greenough’s creation was ready for viewing in the Rotunda.

A photograph (circa 1875) showing Greenough’s statue at the head of East Capitol Street. First Street bisects East Capitol Street in the center of the photo. The future site of the U.S. Supreme Court is above First Street to the left and the Library of Congress above First Street to the right. This photo was taken shortly after the statue was moved to this location. (Courtesy of John DeFerrari)

Moved Outside

View of the Washington statue and pedestal on the U.S. Capitol grounds (date unknown). The pedestal was later used as a corner stone for the Capitol Power Plant. (Courtesy of Wisconsin Historical Society, Image ID: 86720. www.wisconsinhistory.org)

The statue was widely panned. Why was the president wearing a toga with his bare chest exposed? Greenough modeled his creation on the statue of Zeus at Olympus, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Carved on Washington’s chair were images of Apollo riding a chariot and another of the infant Hercules saving his twin brother from a snake. Unfortunately, by this time the neo-classical style was falling out of favor in the United States.

Moreover, the weight of the statue created problems with the Rotunda floor, which needed shoring up to bear the statue’s weight; and the lighting was not good, a situation Greenough complained bitterly about.

All this led to the first move of a multi-stop journey over the next century and a half.

In 1843, the statue was moved outside, again under Captain Easby’s direction, near the east gate of the then Capitol Square, remaining there until 1875. In that year, the statue was transferred opposite the east portico facing the capitol. [see Smithsonian record Washington Statue Transferred to SI | Smithsonian Institution Archives].

Portrait of Elliott Woods, Architect of the Capitol (1902-1923). Woods pressured Congress to move Greenough’s statue of Washington off the capitol grounds to an indoor location. (Architect of the Capitol {{PD-US}})

Criticism continued unabated, leading Greenough to fault Americans for their lack of artistic taste. As late as 1897, a letter writer to The Washington Post called the statue “… a historical, climatic, and sentimental lie.”

Over the years, the statue suffered many indignities.

Vandals broke off the big toe of Washington’s left foot, just sticking out over the edge of the base. The president’s digit was replaced by famed sculptor Lot Flannery, known for his statue of Lincoln that still stands in Judiciary Square.

Crowds eager for a good view of the celebration honoring Admiral Dewey’s victories in the Spanish-American War, used the statue as an observation point. Children stood on the pedestal and on the statue itself; one youngster even sat on General Washington’s shoulders kicking his feet against Washington’s chest.

The delicate Italian marble deteriorated in the rain and snow, forcing authorities to cover it in a makeshift shed for part of the year. At one point, the elements caused damage to the right eye and a large piece near the nose dopped out, giving the face “… a curious expression.”

To The Smithsonian

A 1920 photo of Washington’s statue in the apse of the Commons (sometimes known as the chapel) in the west wing of the Smithsonian Castle. The statue was moved here in 1908. (Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution Archives)

By 1907, the Superintendent of the Capitol Elliott Woods had had enough and implored the Smithsonian to take the statue and house it in one of that museum’s buildings. Congress agreed, and the following year the statue made a slow journey drawn by horses to the Smithsonian Castle. The pedestal on which the statue rested was used as the cornerstone of the Capitol Power Plant at 25 E Street, SE, where the inscription “First in Peace” is still visible.

At the Castle, the statue was placed in the apse of the Commons in the west wing of the building, an attractive setting backed by two rows of arched windows, where it remained safe and warm until 1962.

In November of that year, museum staff moved the George Washington statue from its recess in the Commons, squeezing it through a temporarily removed arched window and frame on the south wall. Once on the ground outside, it was lifted by crane onto a flatbed truck and carried across the National Mall to the Museum of History and Technology (renamed the National Museum of American History in 1980), then under construction.

This was its final home. Since then, millions of people have climbed to the second floor to see Greenough’s creation.

Check out the toe, though; Flannery did a pretty good job.

Greenough’s statue of Washington being prepared to move to the Museum of History and Technology (today’s National Museum of American History) in 1962. A window and frame on the south wall of the Commons was removed to get the statue through. (Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution Archives)

Once the statue was removed from the Smithsonian Castle, it was hoisted by a crane onto a flatbed truck for the journey across the National Mall to today’s National Museum of American History, where it remains today. (Courtesy of Smithsonian Institution Archives)

Sources

Evening star. [volume] (Washington, D.C.), 01 Nov. 1908. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045462/1908-11-01/ed-1/seq-18/>

Edward T. Folliarde . "90 Years- and Peaceful Obscurity." The Washington Post (1923-1954), Jun 30, 1929, pp. 1. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/90-years-peaceful-obscurity/docview/149974864/se-2.

New-York tribune. [volume] (New York [N.Y.]), 19 Nov. 1905. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. <https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1905-11-19/ed-1/seq-19/>

Smith, Wilhelmine M. Easby, and Association of The Oldest Inhabitants Of The District Of Columbia. Personal recollections of early Washington and a sketch of the life of Captain William Easby. A paper read before the Association of the Oldest Inhabitants of the District of Columbia, June 4. [Washington, Beresford, pr, 1913] Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <ww w.loc.gov/item/14020031/>.